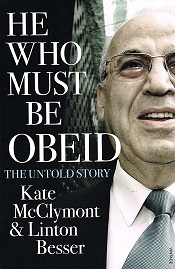

He who must be Obeid. The untold story

Kate McClymont and Lynton Besser

Vintage Books, 2014

Reviewed by Steve Painter

For a book about a political figure, there’s remarkably little politics in He Who Must be Obeid.

That’s not the fault of the authors, who have drawn together in one convenient place a comprehensive account of the 20-year career of a Labor MP who ran the dominant faction in his party for a decade or so, destroying three Labor premiers and eventually killing the golden goose by plunging the Labor Party to a devastating electoral defeat in 2011. Obeid was not much of a politician. He rarely made a speech in his 20-odd years in the parliamentary chamber of the NSW upper house.

Former NSW Labor Party general secretary, now Senator, Sam Dastyari summed up his political contribution: “Eddie was an incredibly influential guy. He had fantastic relationships with everybody. He was very charming, very witty, very likeable.”

This is a leader of Centre Unity (better known as the NSW Labor Right), the faction that likes to present itself as the home of genius, of pragmatic realism, in Australian politics.

Dastyari can think of nothing better than to admit that his faction was taken over by a glib, fast-talking, apolitical influence peddler. Well, Obeid was by all accounts good at raising money for the Labor Party, so he must have been OK.

Obeid’s main political qualification was a beachside house at Terrigal, where young MPs could party their way into what became the dominant NSW Labor faction, known strangely enough as the Terrigals, and the faction would in turn help them shoulder their way through the pack seeking ministerial seats.

There is a tendency to treat Obeid as an aberration, but he’s not. Another reputedly great Labor figure, Graham Richardson, was also a pretty fair influence peddler (aka numbers man) fund-raiser (bagman), so Fast Eddie stood in an honourable tradition.

And Richardson was by no means the first of his type. His mentor was John “Bruvver” Ducker, who dispensed the spoils of office in the Labor Party when Richardson was a young man.

His role as a bagman and numbers man wasn’t Obeid’s only resemblance to Richardson. In 2009, Kate McClymont and Deborah Snow wrote of Hawke and Keating government minister: “When he wants to … he can turn on the charm like few others. He is genuinely good company, self-deprecating and wildly entertaining.”

Like Obeid, Richardson appears to have left parliament with far more in the bank (a Swiss bank, incidentally) than he could ever have earned from a parliamentary salary.

It was Richardson who arranged Obeid’s entre into the inner circles of the Labor Party. He was interested in the printery owner’s wide circle of contacts in the Lebanese community. These could be used as shock troops for branch stacking, an essential skill for a Labor numbers man.

Control of branches meant control of parliamentary endorsements and strong influence in local councils, which was useful when well-heeled developer interests ran up against inconvenient building regulations and other by-laws, and might be suitably grateful if the problem could be made to go away.

The Independent Commission Against Corruption has uncovered corruption on a grand scale involving Eddie Obeid. Rigged tenders, excessive charges for services to Sydney Water, flouting of municipal by-laws and other methods were used to milk tens of millions of dollars from revenue intended to provide services to the people of New South Wales.

Obeid and his collaborators may face prosecution over these matters, but that is by no means certain.

Obeid’s exploits led ICAC prosecutor Geoffrey Watson to famously declare them “corruption on a scale probably unexceeded since the days of the Rum Corps”.

As if to demonstrate how little politics meant to him, towards the end, when Labor was spiraling towards defeat largely as a result of being destabilised by the Obeid faction, the mastermind began reaching out across the political divide, forging alliances in the Liberal Party, a tangled web that entrapped federal Liberal assistant treasurer Arthur Sinadinos, leading to his resignation from the Abbott ministry.

During his 20 years in parliament, Obeid had access to the highest levels of power in the Labor Party and there was almost no part of it that his influence didn’t touch. One of his chief collaborators in later years was a leader of the NSW Labor Left, Ian Macdonald.

It would be easy to dismiss Eddie Obeid as a greedy man who systematically abused an otherwise sound political system for his own financial gain.

But Obeid was by no means the first of his type. I Remember, the memoir of former NSW premier Jack Lang, is crammed with tales of skullduggery and lest anyone think that this is a specifically Labor problem, the career of Liberal premier Bob Askin offers plenty of evidence that it’s not.

He Who Must be Obeid ends with the words: “With an arrogance ill-suiting the circumstances, Obeid boasted that there was only a ‘1 per cent’ chance that he would ever be prosecuted. After all that he had been through, Edward Obeid OAM still didn’t get it.”

Obeid may not have “got” some things, particularly the idea of a political career as service to the public, but he certainly “got” the main point of NSW Labor Right politics: this is how capitalism works and this is how power is administered.

Obeid didn’t create that situation. He just walked into what McClymont and Besser describe as an “Aladdin’s cave”, and helped himself.

NB: The views and opinions expressed in this piece are solely those of the original author. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of St George Greens.